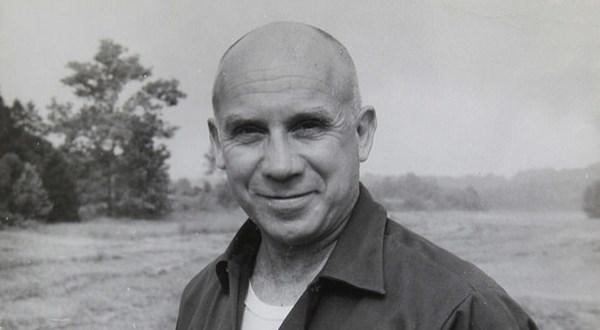

Thomas Merton, the famed spiritual writer, died on 10 December 1968. His writings are still as relevant as his life story is fascinating, particularly his treatment of ‘difference’, a word that ‘now commands an attention that would never have been possible fifty years ago,’ writes Michael Barnes SJ. The fiftieth anniversary of Merton’s death, particularly as it falls in Advent, is an opportunity to contemplate with him the action of the Spirit.

It is fifty years since the death of Thomas Merton, the finest spiritual writer of his generation and a prominent icon of interreligious dialogue. By a strange chance, an even more influential Christian writer, the Reformed theologian Karl Barth, died the same day – 10 December 1968. The circumstances of their deaths could scarcely have been more different. Barth slipped away peacefully at home in Basle aged 82, widely regarded by both Protestants and Catholics – and by no less a figure than Pope St Paul VI – as the greatest Christian theologian since Aquinas. Merton was killed in a freak accident while at a conference in Thailand. He was aged 53; it was 27 years to the day since he had entered Gethsemani Abbey in Kentucky in 1941.

Two very different lives, two very different deaths, two very different journeys of faith. A Protestant theologian at the very centre of Catholic Christianity, a Catholic contemplative on the edges of a Buddhist world. Separated by age and religious affiliation, Barth and Merton seem an odd couple to arrive in the heavenly judgment hall at the same moment. Do they add anything more than a couple of powerful footnotes to that crazy year of 1968, a year of violent protest, ecclesiastical turmoil and political assassination? Or, fifty years on, does such a ‘strange chance’ help us to put our memories together differently, to appreciate how even the tragic loss of a great writer at the height of his intellectual powers can act as a sign of hope?

That very word ‘difference’ now commands an attention that would never have been possible fifty years ago. Merton died a few years after the end of the Second Vatican Council and it is impossible to guess where his explorations into hitherto forbidden territory might have taken him. But even a brief glance back at his life is enough to highlight what we now take for granted: experience of ecumenical – not to say interreligious – relations, at both practical and theological levels, has dramatically altered the way we look at our increasingly globalised world.

The depths of God’s freedom

Let’s stay with the odd couple for a moment. The intensity of their writing was, of course, matched by a passion for justice and truth. Barth will always be known for the determination of his resistance to the forces of evil unleashed by the Nazi menace; Merton in the last period of his life became notorious for his active support of the civil rights movement and his denunciation of the Vietnam War. But what drew them both was the articulation of a faith that understood intuitively the nature of the redemptive desires of God for human beings. While theology may feel at times like recondite musings for the initiated elite, for both Barth and Merton it is spiritual practice in its own right, founded on a prayerful address to God performed ‘on one’s knees’. They shared the same thirst for a theology that plumbed the very depths of the abyss that separates yet unites human and divine freedom.

The younger Barth was dominated by the dialectic of revelation and religion, the gratuity of divine love set against human striving for self-justification, what he summarily dismissed as ‘unbelief’. In the last decade of his life Merton became deeply influenced by Barth, but with an intuitive feel for a natural theology that Barth could never countenance, Merton sensed something of a paradox about the mystery of the self-revealing God. If Barth had ever read Merton, he would probably have acknowledged him as a typical example of the ‘Catholic And’.

Merton fitted the mould of the generous-hearted Catholic intellectual, versed in the classical theological traditions of Aquinas and Augustine, familiar with philosophers and poets from Dante to Hopkins, and open to all manner of spiritual wisdom. As he says in the Preface to Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, in the changed climate of the Second Vatican Council, for a Catholic to share the experience of a Protestant ‘no longer requires apology or justification’.[1] Friendly tussles with the likes of Barth and Bonhoeffer take their place in a series of observations, from local politics to more distant conflicts and crises, that cluster around his personal ‘still point’, the monastic enclosure that makes contemplation in the broadest sense possible.

Unlike Barth, whose Church Dogmatics is one long act of prayerful reaching out in love and obedience to the God who draws him, Merton’s theological landscape embraces difference as he seeks to come to terms with the many ways in which the traces of God’s love are to be encountered in the world. At points one can hear him musing that, if the Word of God is to be heard both at Sinai and in the depths of the heart, what about the voice of the stranger? Can any limits be put on the action of the self-revealing God?

The question is not whether there are limits to the gracious action of a loving God but how one learns to speak about it, how what is known about the God revealed to faith is made to cohere with what is strictly unknown and only dimly discerned in hope. The ‘older Barth’ – unlike Merton he had many years to grow mellow as he sought better ways to speak of the utter sovereignty of God – would have stuck with the principle with which he begins the Church Dogmatics: ‘there can be no dogmatic work without prayer’.[2]

A simple enough statement but, as Barth and Merton and every theologian worth their salt knows, it begs the question of how human desires are channelled through prayer, how prayer as a contemplative attentiveness to the divine is itself formed. Prayer is an act of human beings in all their fallibility. And, whether we like it or not, it is alloyed with memories and images and touched by deep feelings and aspirations, whether of joy or remorse. The classical traditions of prayer in all religions (most especially Buddhist forms of meditation and mindfulness that Merton came to admire) recognise the danger of turning inner movements into idols of the imagination. They counter by commending virtues of humility and indifference, equanimity and obedience. Such is the discipline of prayer, learning how to wait and receive the grace of a holy detachment.

Barth appreciated the point better than most and refused to countenance any mode of being and acting by which human beings could somehow rise to God. Yet Merton spots a flaw, if not in the logic of Barth’s exposition, then in the epistemic conditions that surround his focus on the irreducibility of Christian language about God. Just how ‘pure’ can those conditions ever be? Merton’s contemplative vision of a world transformed by God’s Word grew out of the routine of the religious community, rooted in the liturgical tradition of the Church, filled with its rhythms and touched by its beauty. If there is a parallel in Barth it comes from his practice of beginning each day by listening to Mozart.

The music of the Spirit

This is where Merton’s ‘difference’ from Barth becomes subtly instructive. The first part of Bystander is entitled ‘Barth’s dream’. Merton comments on Barth’s experience of being deeply disturbed by Mozart’s rejection of Protestantism. For Mozart insists Protestantism is ‘all in the head’ and knows nothing about ‘the meaning of Agnus Dei qui tollis peccata mundi’. So in his dream Barth finds himself appointed to examine Mozart’s theology. But, despite Barth alluding pointedly to Mozart’s Masses, Mozart answers not a word. ‘I was deeply moved by Barth’s account of his dream’, writes Merton, ‘and almost wanted to write him a letter about it. The dream concerns his salvation, and Barth perhaps is striving to admit that he will be saved more by the Mozart in himself than by his theology.’[3]

Mozart’s music speaks as a paean of praise to the beauty of creation, acting almost as a natural theology in its own right. The child prodigy who produced work of such sublime perfection raises the possibility that human effort can somehow rise to God, that the dialectic of faith and works is not that neat and straightforward, that God’s grace can filter through the most unlikely channels. Merton finishes the interrogation with this gentle brotherly reproof: ‘Fear not, Karl Barth! Trust in the divine mercy. Though you have grown up to become a theologian, Christ remains a child in you. Your books (and mine) matter less than we might think! There is in us a Mozart who will be our salvation.’[4]

Merton’s father was an artist; a very good one, in Merton’s judgment. And in the last few years of his life, back in his hermitage at Gethsemani, Merton himself took up photography. With a keen eye for the visual, he became more and more entranced by the simplicity of his surroundings, by a God revealed in the everyday. If the spare beauty of the Cistercian chant gave him an insight into what was happening in Barth’s inner depths as he listened to his beloved Mozart, Merton’s own aesthetic experience began to take on ever new forms as he found his own ‘inner child’.

What took Merton to Asia on that last long journey into another universe of meaning was more than dissatisfaction with the constraints of the monastic life or an insatiable curiosity about the borders of his own tradition. Both Barth and Merton were writers, and writers are artists, called not just to feel but to take the risk of communicating feeling, refreshing traces of a Word that resonates with the classical tradition but presses its limits. Merton spent his life picking up the words of others, written and oral, the intricate meditations of theologians and the throw-away comments in the newspapers, seeking to give them a different shape and a new direction. And yet, as he discovered, ‘the other’ has a way of speaking back in ways that cannot easily be understood, let alone communicated.

The liberty of the Spirit

On that fateful December day, fifty years ago, Merton had delivered a lecture on the unlikely topic of ‘Marxism and Monastic Perspectives’. He finished by sharing his conviction that

by openness to Buddhism, to Hinduism, and to these great Asian traditions, we stand a wonderful chance of learning more about the potentiality of our own traditions, because they have gone, from the natural point of view, so much deeper into this than we have. The combination of the natural techniques and the graces and the other things that have been manifest in Asia and the Christian liberty of the Gospel should bring us all at last to that full and transcendent liberty which is beyond mere cultural differences and mere externals – and mere this and that.[5]

At that point he drew to a close, saying he would return later in the evening for the panel discussion and uttering words that would be banal were it not for their prophetic finality. ‘So I will disappear.’

If he had lived, Merton would have returned to his hermitage at Gethsemani ready to turn the very full notes recorded in his Asian Journal into profound and elegant theological reflection. It’s impossible to guess what direction he would have taken, of course, but it is highly likely his commentary would have revolved around one extraordinary moment when he visited the ancient Buddhist sites of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa in central Śri Lanka. Here he talks about being almost forcibly jerked free from his ‘habitual, half-tied vision of things’ yet also realising that ‘there is no puzzle, no problem, and really no “mystery”.’

The rock, all matter, all life is charged with dharmakaya … everything is emptiness and everything is compassion. I don’t know when in my life I have ever had such a sense of beauty and spiritual validity running together in one aesthetic illumination. … This is Asia in its purity, not covered over with garbage, Asian or European or American, and it is clear, pure, complete. It says everything: it needs nothing. And because it needs nothing it can afford to be silent, unnoticed, undiscovered. … The whole thing is very much a Zen garden, a span of bareness and openness and evidence, and the great figures, motionless, yet with the lines in full movement, waves of vesture and bodily form, a beautiful and holy vision.[6]

It feels as if his version of ‘Barth’s dream’ has awakened a dormant passion, as if the Buddha-images provoked a new way of understanding the intellectual quandaries provoked by the human desire for salvation. For years the dialogue between Christianity and Zen had been a constant preoccupation for Merton, conducted largely through correspondence, not least with the great Zen teacher, D.T. Suzuki. In the Preface to a collection of essays dealing mainly with ‘Oriental religion’, published a year after the end of the Second Vatican Council, Merton explains that he is not concerned ‘merely to look at these traditions coldly and objectively from the outside but, in some measure at least, to try to share in the values and the experience which they embody.’[7] Some ten years earlier, the first reference to Zen in his journal records an intuition that arises from his own Christian faith. Zen, he says, ‘in its fundamental psychological honesty [is] inseparable from the interior poverty and sincerity Christ asks for’.[8]

He had come to understand the intellectual and spiritual coherence of Asian traditions without feeling the need to make them a substantive part of his contemplative practice. Yet now a new sense of the significance of difference begins to emerge. He is knocked off his guard by an unexpected aesthetic experience that is much more than that: a ‘holy vision’ that has an integrity all of its own – and demands a response.

As a master of his craft, Merton the artist-writer finds himself struggling to voice what approaches him through an entirely different religious idiom. His description of what he sensed at Polonnaruwa has become something of a ‘classic’ in its own right. To that extent it is much more than a ‘mystical moment’ in a single life but an event that both shakes and confirms. ‘Holy equanimity’, the condition of a prayer that lets God be God, is only holy when it is open to disturbance, to not having the last word. What Merton touched – what touched Merton - continues to provoke further responses in a world more deeply sensitised to the complexity and darkness of ‘religion’ than either Barth or Merton could possibly have known.

Watching for the light

On anniversaries like this thoughts naturally turn to ‘legacy’. In his case studies of types of mysticism William Harmless uses the image of Merton the ‘fire-watcher’.[9] During his early years in the monastery, Merton would take his turn to go on patrol, looking out for any sign of a spark that might destroy the sleeping monastery. And being Merton he would write about the experience, building up the keen sense of the natural observer, sometimes the ‘guilty bystander’, sometimes the prophet of danger and darkness. Yet observation is not enough; he asks us to embrace difference.

What transforms the inner work of struggling with the Word is no mechanical adjustment of present concerns to the demands of a normative tradition but something set into the hearts of human beings, a more demanding and personal adjustment to the mysterious action of the Holy Spirit. Quite how the Spirit prompts us, evoking memory, awaking echoes, stimulating links and connections, is infinitely mysterious. But contemplative attention cannot be separated from ascetical discipline, any more than any act of communication can afford to overlook the painstaking craft of working with words, whether written or spoken.

Both Merton and Barth dealt in very different literary genres, but what they produced were truly works of art, magnificent testaments to the religious imagination that continue to inspire and entrance. This is no mere artifice, a contrived rhetoric that seeks to make a case against some imagined other. What they share is the instinct, manifest in the lives of contemplatives in every religious tradition, that they are confronted by the magnificent otherness of Creation that is only ever mediated through created things. Yet, paradoxically, in their being grasped and responding to the empowering experience of the Word that is beyond words, speech becomes possible, a halting speech no doubt, but one that – for the Christian contemplative, certainly – is understood as a Word that is addressed to all manner of people and in all manner of idioms.

Maybe that’s what Merton came to see. The books matter less than the Spirit that inspires them. The tragedy of a life cut short is only tragic in the sense that the perplexing intuition of a fullness of all things in God can only ever be glimpsed and never fully articulated. The tragedy lies in not learning the lesson of Advent, that human lives are founded not on the assurance of what can be safely spoken but on the hope that continues to wonder at the beauty and mystery of each moment of Creation. For Merton the monk, what made such a contemplation possible was the rhythm of the liturgy and the annual cycle of Christian prayer, the ascetical ‘platform’ on which the Spirit could act.

Maybe one way to celebrate a remarkable writer who continues to inspire admiration and controversy in equal measure is to ponder on a few words in his autobiography when he speaks of the day he entered the monastery – the same date, remember, that he died.

Liturgically speaking, you could hardly find a better time to become a monk than Advent. You begin a new life, you enter into a new world at the beginning of a new liturgical year. And everything that the Church gives you to sing, every prayer that you say in and with Christ in His Mystical Body is a cry of ardent desire for grace, for help, for the coming of the Messiah, the Redeemer.[10]

Michael Barnes SJ is Professor of Interreligious Relations at the University of Roehampton.

[1] Thomas Merton, Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, London: Burns and Oates; 1968; p vi.

[2] Church Dogmatics 1/1.23.

[3] Conjectures, p 3.

[4] Conjectures, p 4.

[5] The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton, edited from the original notebooks by Naomi Burton, Patrick Hart and James Laughlin; London: Sheldon Press; 1974; p 343.

[6] Asian Journal pp 233-6.

[7] Thomas Merton Mystics and Zen Masters, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 1967: p ix.

[8] In A Search for Solitude: the Journals of Thomas Merton, Volume 3; edited by Lawrence S Cunningham, Harper: San Francisco; 1995: pp 139.

[9] William Harmless, Mystics, Oxford: OUP; 2008: pp 37ff.

[10] The Seven Storey Mountain, from A Thomas Merton Reader, edited by Thomas P McDonnell, London: Marshall Pickering; revised edition 1989; p 152.