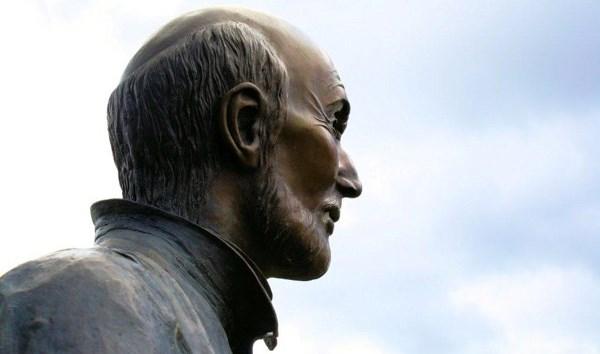

The Feast of St Ignatius Loyola on 31 July is being celebrated this year amid preparations for two other important commemorations: the centenary of the outbreak of World War I, and the bicentenary of the restoration of the Society of Jesus. With these anniversaries in mind, Philip Endean SJ explores the martial imagery associated with the founder of the Jesuits: what is the appropriate response to the tradition of ‘Ignatius the soldier-saint’ in the modern age?

St Ignatius first came into my life as the soldier-saint. I was a little boy in a British Jesuit school. The three or four hymns to Ignatius in the in-house collection drew on this image quite unselfconsciously. We borrowed, bizarrely, the tune to ‘O purest of creatures’, a standard Marian hymn, and cheerfully sang:

Dear Soldier of Jesus, Our Lady’s brave Knight!

Bestow on your sons in the van of the fight

The ward of your shield and the might of your sword,

For God’s Greater Glory, for Christ Our dear Lord!

With His Cross as your beacon, and heaven your goal,

In fasting and watching and searching of soul,

You fought at Manresa until you had won,

And Mary accepted the vows of her Son.

Things had become rather different ten years later. As a young adult thinking about becoming a Jesuit, I was given a splendid book, one that ought to be revised and revived: Tom Clancy’s An Introduction to Jesuit Life. One of its appendices trenchantly discredited the idea of Ignatius as soldier-saint. The youthful Ignatius had been a trained courtier, not a solder. In the household of the royal treasurer, he had learned games, dances, etiquette, literature and administration. Horsemanship and the dagger had been mere sidelines. ‘Arévalo was no West Point.’ Ignatius’s involvement in a couple of skirmishes was merely ‘a phase he went through’; his military career ‘brief and singularly undistinguished’. To call Ignatius Loyola a soldier-saint made as little sense as to call John Kennedy and Richard Nixon sailor-presidents.Manifestly, the soldier-saint had fallen out of fashion. At any rate, whatever the truth of Clancy’s arguments, the Ignatius on offer in the hymnbooks had become more introspective and thoughtful, less blatant. He was no longer the heroic soldier inspiring community singing, but rather the individual, open-hearted retreatant, crooning ‘Take, Lord, receive all my liberty’.

The Chastening of the Trenches

In 2014, Ignatius’s feast falls during the centenary of World War I’s initial exchanges. Perhaps that fact—though obviously amid much else—helps to explain the eclipse of the military Ignatius from public Jesuit piety.

The generations immediately preceding my own had lived through world war. Understandably, they pressed that experience on to us. Compelled as we were into the army cadet force, we were given ‘the Queen’s uniform, in which your ancestors fought and died.’ I focussed my resentment by claiming that submitting us to military training was the equivalent of providing us with contraceptives. After all, in both cases it was a matter of putting sensible precautions in place for when proper morality broke down. But even my adolescent self could recognise that this argument, however logical, was insensitive. It lacked contact with lived reality—even if that reality’s pain and grief were being hidden in a false rhetoric of toughness.

It took time for us to become aware of war’s psychological and cultural scars. During the event and the aftermath, humankind could not bear very much reality. Only during the long 1960s could we begin, with artistic works like Joan Littlewood’s Oh what a lovely war and Britten’s War Requiem. Sebastian Faulks’s magnificent 1993 novel, Birdsong, well evokes this gradual awakening. It is Elizabeth in the 1970s who gradually pieces together what had happened in the trenches to her late grandfather, Stephen Wraysford—a figure who had died young long before she was born, permanently damaged by his experience. Wraysford survives the massacre at the Somme in July 1916, an event that had prompted a chaplain to throw away his pectoral cross and simply fall to the ground with his head in his hands. Those who looked on ‘knew what had died in him.’

People needed time before such memories could emerge into consciousness. Elizabeth is dependent on faint memories conveyed by Stephen’s commanding officer in extreme old age down a telephone. At one point she visits what seems to be the Thiepval arch, a massive structure with British names carved in every grain. A man sweeping nearby tells her that these names refer only to the missing, not the buried dead, and only to those in the fields nearby, not the whole war. ‘Nobody told me’, she reflects; ‘my God, nobody told me.’

When the Elizabeths of the mid-twentieth century rediscovered the Tommies of World War I, they thought first of traumatized victims, of young men betrayed by their parents and governments. Admiration of their heroism and generosity, though not false, seemed misplaced. Any religious interpretation in terms of being with Christ follows the lead of Wilfrid Owen, for whom ‘in this war he too lost a limb’. No wonder we became queasy about Ignatius as a soldier-saint.

A Company Re-established

In 2014, Ignatius’s feast also falls within a novena ending with the bicentenary of his Society’s re-establishment on 7 August 1814, following its 41-year suppression. Might we somehow re-establish Ignatius the soldier-saint? Is some other response to this tradition possible, besides crass exuberance or embarrassed silence?

Shortly after the Society’s re-establishment, Fr General Jan Philipp Roothaan wrote to Jesuits throughout the world commending the study and practice of Ignatius’s Spiritual Exercises. Roothaan’s text, at the beginning especially, has an elegiac quality, evoking a lost heroic past. The Jesuits of Roothaan’s generation cannot hope to imitate those gifted with the first fruits of the Spirit, fruits that had come forth in the biblical hundredfold. The most that can be hoped for is a shift from tenfold to sixtyfold.

But Roothaan’s letter also hints at something deeper. In this new situation of felt poverty, Roothaan encourages Jesuits to look again at Ignatius’s original text, and to unlearn conventional elaborations that might now be unhelpful. The Society’s advancement and success depends not on what it had known previously, ‘on any natural or human support, on the lustre of erudition, on the pomp of eloquence, or on the patronage of others, but on its own principles and spirit, perpetuated in our hearts’. If we strip the tradition down, we may find unexpected power.

In the Spiritual Exercises, Ignatius does indeed encourage us to think of ourselves as soldiers, enlisting under Christ as eternal Lord, with the aim of conquering ‘all the world and all enemies’. But just as, in the synoptic gospels, Jesus’s triumphant proclamation of the Kingdom becomes caught up with the mystery of the cross, so in Ignatius what starts as a crusade in the outer world quickly becomes a confrontation with hidden selfishness within, a delicate negotiation of practical options, and perhaps an encounter with painful humiliations. Ignatius, let us not forget, carried his war wounds for life. Ignatius’s achievement depends on something more than exuberant youthful generosity. What made him a great saint was what he did once his soldierhood had gone sour.

Perhaps the history of the restored Society, which Roothaan did so much to build up, illustrates the same pattern. It became in some ways more numerous and successful than its predecessor, not least because of skills of negotiation and adaptation in situations where Catholicism was not the cultural norm.

One of Gerard Manley Hopkins’s later poems has traditionally (he left us no title) been called ‘The Soldier’. This title is in some ways misleading. Quite apart from the fact that the poem deals as much with sailors as soldiers, its central theme is about how we respond to iconic images. Though ‘our redcoats, our tars’ are in large part ‘but frail clay, nay but foul clay’, we nevertheless instinctively bless them. Why? Because the human heart ‘gives a guess that, hopes that, mákesbelieve’ that the uniform betokens a truth:

It fancies, feigns, deems, déars the artist after his art;

And fain will find as sterling all as all is smart,

In the second part of the sonnet, Hopkins extends the point. Christ shares this positive instinct, and in so doing both widens the scope and uncovers a theological foundation:

Mark Christ our King. He knows war, served this soldiering through;

He of all can reave a rope best. There he bides in bliss

Now, and seeing somewhere some man do all that man can do,

For love he léans forth, needs his neck must fall on, kiss,

And cry ‘O Christ-done deed! So God-made-flesh does too:

Were I come o’er again’ cries Christ ‘it should be this’.

It is not just soliders whom Hopkins’s Christ embraces, not just sailors with whom Hopkins’s Christ identifies. The message applies to anyone doing their reasonable best—perhaps even Hopkins himself, as he struggled to educate Dublin’s reluctant adolescents.

In Ignatius’s Exercises, ‘the call of the temporal king … helps to contemplate the life of the king eternal’. We do not stay with the heroic image; we are moved beyond it. In its turn, our imagining ourselves as responding soldiers hooks us, gradually, into a divine solidarity at once more inclusive and subversive, with Christ playing ‘in ten thousand places / Lovely in limbs and lovely in eyes not his’.

The process is difficult, challenging, conflictual. Trench warfare, and its nuclear successors, have no doubt subdued our enthusiasm about soldiering; martial imagery may have become spiritually toxic, to be used only with great care. We can no longer hear such talk innocently or romantically. But nothing that has happened in the age of industrial war seriously undermines what Ignatius was really doing with his soldier image.

Philip Endean SJ is Professor of Spirituality at Centre Sèvres, Paris.